2022-10-25: Drivers of Open-Source Adoption

Why has open-source software adoption been so successful in some areas, but lagged or even barely appeared in others? Most web applications you use are likely built on top of an entirely open source stack—from the operating system up through the JavaScript framework. Yet most likely the application itself—along with the deployment infrastructure serving it—is locked behind closed doors. Why?

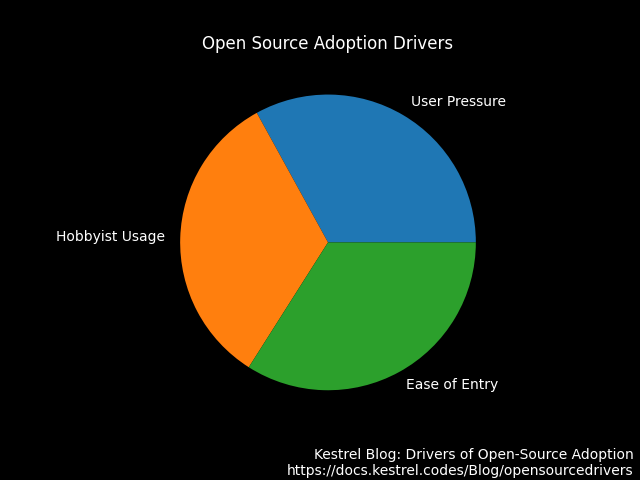

There are three fundamental drivers behind open source adoption—pressure from professional users, interest and adoption among hobbyists, and relative ease of entry.

Professional User Pressure

Pressure from professional users of a product creates an obvious incentive to consider open-source licensing. Being able to inspect the source code of the library or framework you're using is a powerful tool that developer power-users have become so reliant on that many may not be able to recall the last time they had to rely on a software library solely through its exposed API and documentation. Many modern software development platforms don't even conceptually support the idea of a closed-source library package anymore (though workarounds and obfuscators continue to serve their purpose for those unwilling to embrace the open standard). And even among non-developer user bases there might be good reason for users to push for open source development—such as when it leads to a robust plug-in ecosystem.

Hobbyist Interest

Hobbyist interest and adoption provides a natural route to organically growing a user-base prior to maturity. While professional users are unlikely to embrace early stage open source projects that haven't been battle-tested and lack an established support community, hobbyists are happy to experiment with unproven projects—especially when they are available for free. With a user-base established, such open source projects can grow a contributor base and reach a level of maturity that they start to infiltrate the more professional user base.

Ease of Entry

Finally, ease of entry, while self-explanatory—the "easier" it is to provide a new open-source alternative, of course the more likely you are to see some pop up—manifests itself in perhaps surprising ways. Implementation complexity is actually not, seemingly, a significant barrier to entry. After all, the more complex a problem is, the more enticing it is to a curious developer with time on their hands. Some of the most successful open source projects have in fact been those that tackled some of the most complex problems—operating systems; programming languages; databases; development frameworks. In fact it's one of the hallmarks of open source development that it seems to manage complexity better in many ways than traditional closed-source development.

So what are the actual barriers to entry for open-source software? The simplest one is the most paradoxical—when free software isn't free.

We'll dig into this more in the examples, but in brief—the open source software model works well when it's something you can just download and run. When it's something that requires non-trivial compute, infrastructure, or non-zero (even minimal) maintenance costs to deploy and use effectively, the model breaks down. This is not an inherent shortcoming of the model; rather, it's a market failure that prevents the power of open source development from being applied to a vast—and important—class of software problems.

Examples

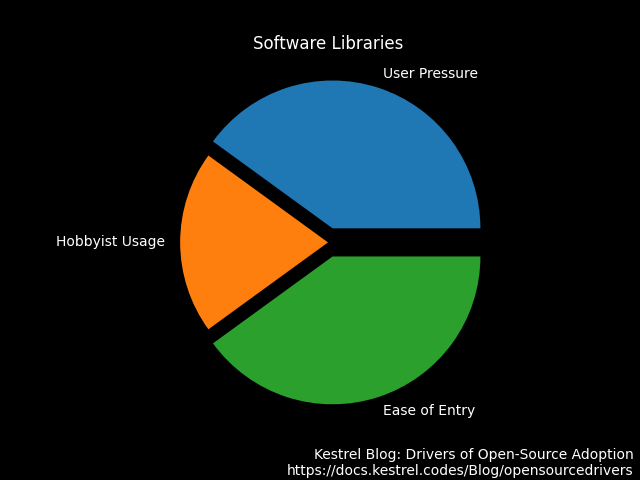

Software Libraries

Software libraries check all of the boxes for open-source adoption. They especially excel in terms of professional user pressure and ease of entry. Developers are themselves naturally the most interested in being able to introspect into and alter the source code of the tools they use. In terms of ease of entry, for most development platforms, making your new open source library available is no more difficult than adding it to a common software repository, from which it can be typically be installed via a single command.

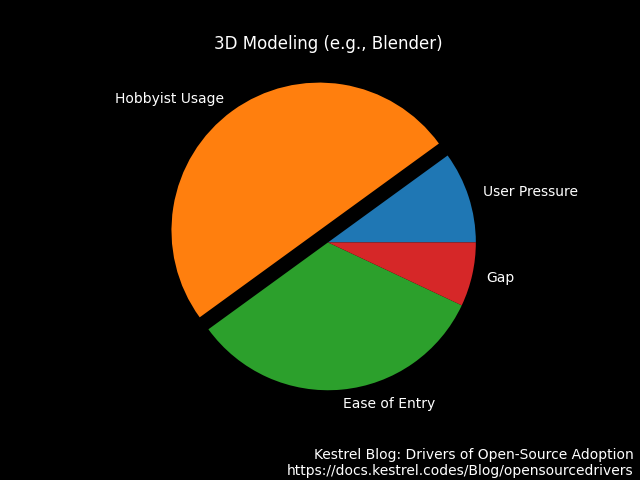

3D Modeling

3D modeling is an example of a very complicated implementation, but where distribution is still as easy as compiling an installer and making it available for download. Blender has of course become the industry standard for 3D modeling, but it wasn't a foregone conclusion—not many 3D modeling users care much about the licensing model for the source code of the applications they use, so the lack of user pressure (along with a somewhat higher barrier for entry, given that users had to discover it through word of mouth and seek it out themselves) meant there was a gap that had to be overcome for Blender to be successful. But given the immense support and interest from the hobbyist community, it was surmountable.

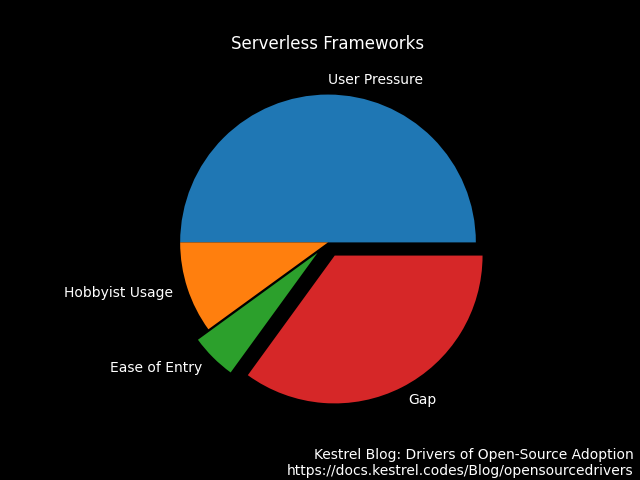

Serverless Frameworks

Serverless frameworks are an interesting example because, similar to software libraries, the developer pressure to have access to the source and deployment code is immense. Complaints among potential users of serverless frameworks—that they are difficult to write tests against, or to integrate into the CI/CD system—would all be solved easily if the frameworks themselves (along with dev deployment instructions) were distributed openly. Yet there are so few examples of open source serverless frameworks that many users don't even think to ask for it. And looking at this chart, it's no surprise why—the barrier to entry is immense, creating a massive gap.

If you're going to build and make available a serverless framework, the presumption is that you will also deploy that framework somewhere where users can make use of it. After all, the benefit of serverless development is that you (as a user) don't need to worry about the deployment environment. Yet deploying it means inherent maintenance costs—you are now responsible for running the compute infrastructure to keep the serverless service running. That means either you eat the cost and hope it doesn't get too popular, or you come up with a business model to support your project that charges users on some form of usage tier.

And that's the main kind of barrier to adoption that many hypothetical open source projects face—the need to develop, in tandem, a sustainable business. Developing an open source project is easy—it's fun, maybe it gets popular or maybe it doesn't, it doesn't really matter. Developing a business is, frankly, kind of a pain; at least for (most of) the kind of people who are interested in coding a side-project. And maybe it would be worth the trouble to figure out how to accept (ugh) credit card payments if you thought you'd stumbled upon some great new business but let's be honest—you're most likely buying a whole new kind of trouble all to bring in $50, maybe $100 MRR?

The Kestrel Model

The fundamental driver behind the Kestrel substructure is not to try to sell developers on the idea that their side-projects are going to make them wildly rich; but rather that it opens the door to a whole new class of open-source projects that they can build, deploy, and get people using all without having to worry about how they're going to pay for it. By offloading the infrastructure costs to the users rather than the creators, Kestrel is designed to allow creators to focus on their creativity and curiousity. In the end creators are compensated appropriately for projects that get broad usage but more generally they just don't need to worry about it.

Kestrel is under active development; follow @SubstructureOne on Twitter to get updates on development progress.